MSc Computer Game Development module – recreating the 1981 arcade classic ‘Defender’ – wish me luck…

Portfolio pieces and links

Here are some links to project pieces I have been working on through the second year of my computer game development degree course:

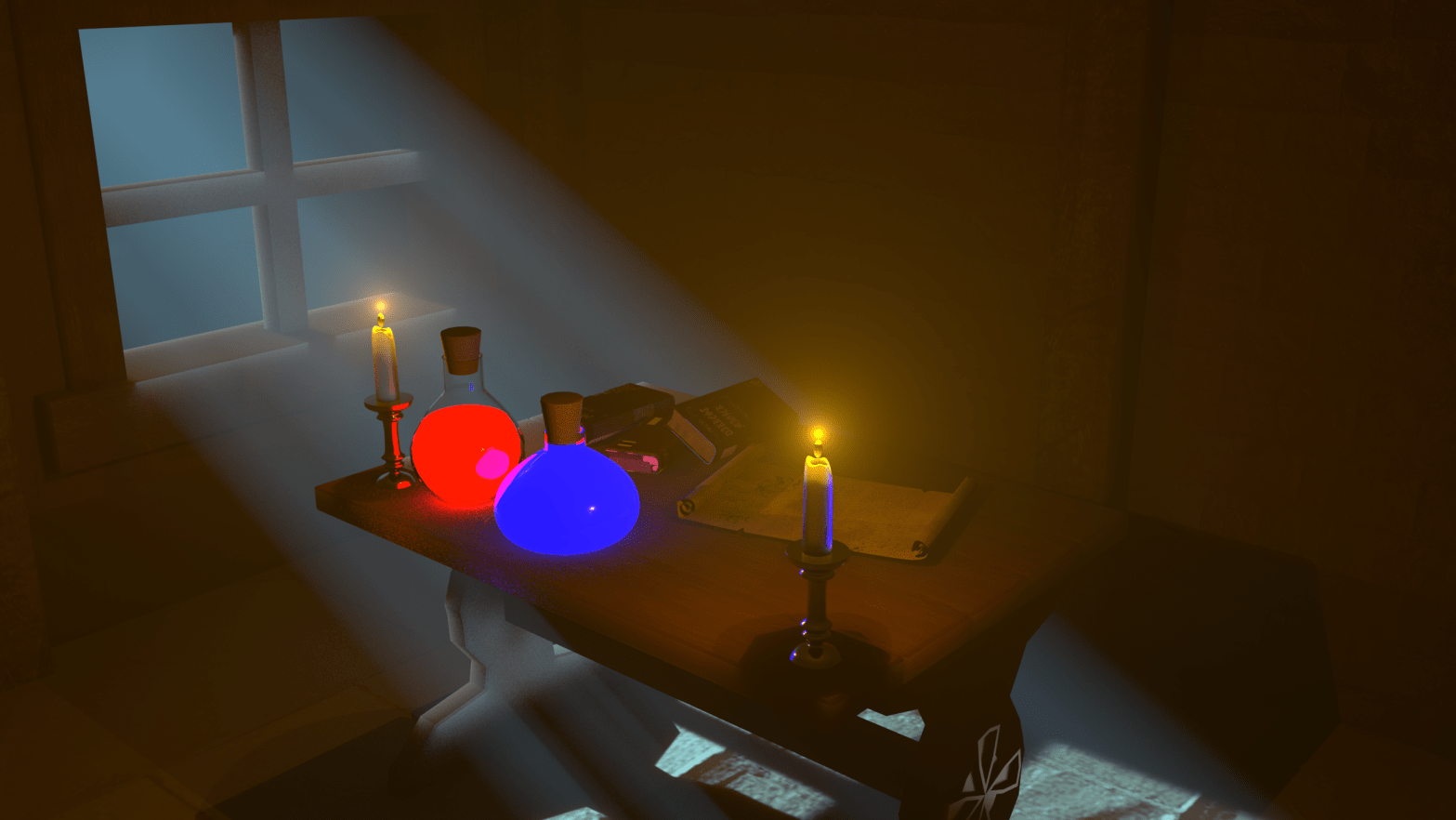

The above project was for a 3d modelling and animation in game engines module created during December 2022 – January 2023.

Artstation link:

https://geoffwinton.artstation.com/projects/6b95LO

3rd Year Projects:

Producing game ready assets using photogrammetry!

Artstation Link:

https://geoffwinton.artstation.com/projects/LR0GQw

2025 already! Latest work in progress – recreate the 1981 arcade classic ‘Defender’ – early stages.. Video of the finished product to follow!

Maya 3d modelling portfolio

This page will feature screenshots of my 3D modelling work made in Maya and Substance Painter

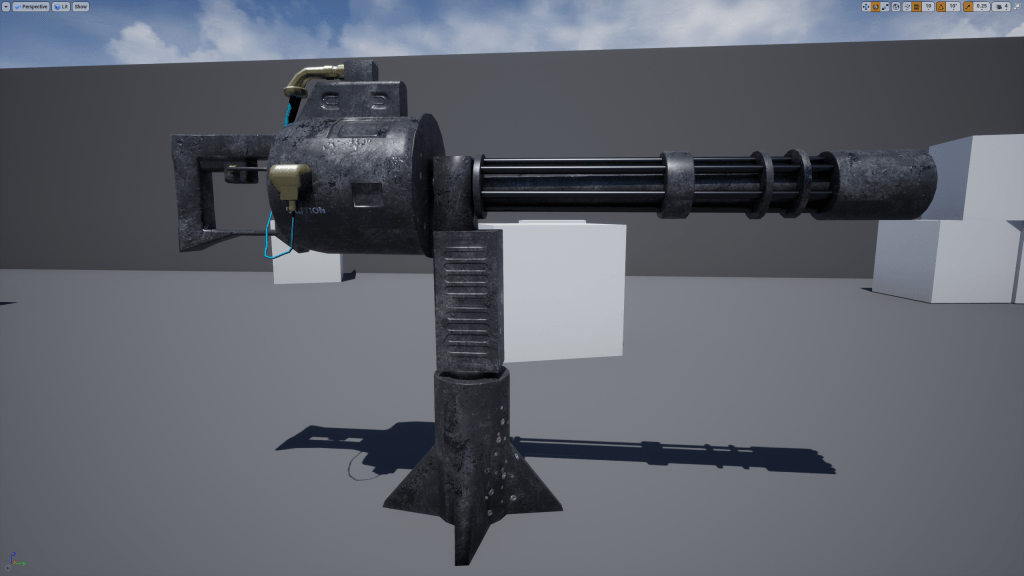

Mini-gun made for Glyndwr University first year project 2022

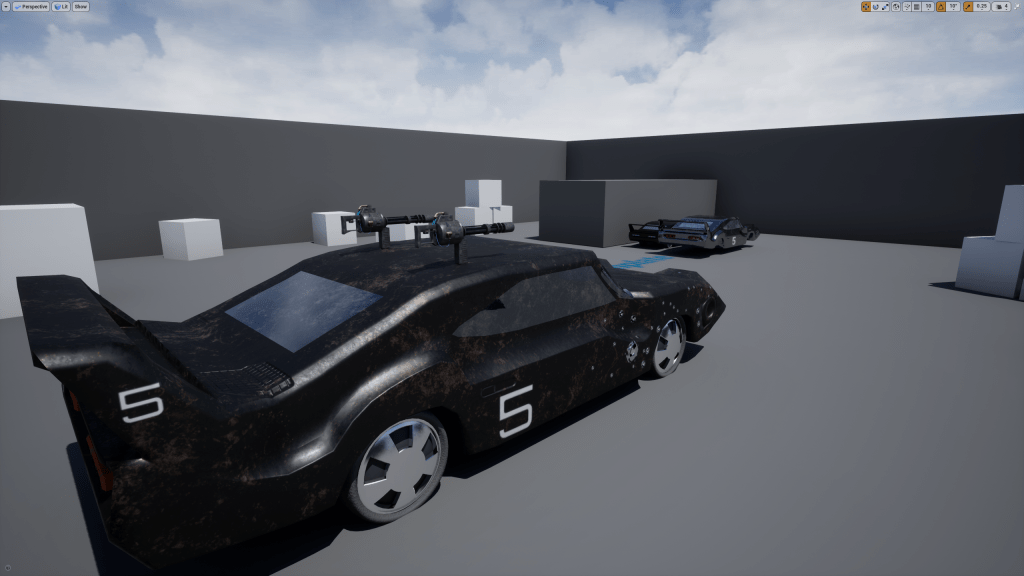

‘Death Race’ style car created for the same project 2022

Above is a cinematic trailer made with 2 other students for a first year project at Glyndwr University

Glyndwr University Computer Game Development Foundation Year – A reflection

Having made the firm decision to return to full time education or face heading towards retirement in some boring, badly paid or physically demanding job (I had just spent 4 ½ years landscaping and knew at 47 I was getting too old for it) I went looking for a computer related course.

As soon as I came across the game dev course in Glyndwr, Wrexham I felt a wave of excitement and knew instantly it was what I wanted to do. A pure computer science degree seemed mind numbing by comparison and with a life-long passion for gaming and a longing to do something more creative, it was the obvious choice.

Having been away from higher education for 25 years it made sense to take on the foundation year. An opportunity to get used to full time study again after a long break, and chance to build my skills to a level where I would not feel overwhelmed. A head-start if you like.

The year was to be split into two semesters with 3 modules taught in each semester.

Due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, the teaching for the whole year was anticipated to be done purely online as proved the case. I was unsure how successful this would be as it was a new situation for both students and lecturers to deal with, but it worked extremely well.

Semester One

The first three modules comprised of Design & Technology, Game Studies and a module titled ‘The skills you need’. Each with its required assignments to be completed.

Design & Technology involved working as a pair on a mobile phone application design of our choice. Starting with a Jackson Structured Program (JSP) design, pseudocode and initial wireframes, and progressing onto an interactive powerpoint and console application coded in C#.

I quickly settled on the idea of a ‘PC Builder’ app, one that would give the facility to produce a list of parts for a build, offer approximate prices, offer links to suppliers and review sites and provide a compatibility check to ensure all parts would function together.

My project partner said he would prefer to do the art side of things, so he did the wireframes and interactive powerpoint while I did the JSP diagram, pseudocode and eventually the C# console application.

I feel like the project went quite well and enjoyed it, although learning C# from scratch and getting the application to work was a real challenge! In retrospect I would certainly have spent more time getting familiar with object-oriented programming techniques in C# before I started coding. The final console application took hundreds of lines of code and a lot of time to get functioning properly. It could have been done in a lot simpler fashion and I learned a lesson there!

Game studies was an essential subject for anyone hoping to go forward and learn to design and develop computer games. With two assignments we were given a good grounding in how games work, what keeps players playing, and techniques involved in taking a concept to prototype, testing and further iterations of the process.

The first assignment was an informal blog on one of our favourite games, a chance to ‘tear it apart’ and examine the finer points of the mechanics and design, enabling us to work out exactly why we love it so much. I chose ‘Subnautica’ and relished the chance to play through it again with a different view on the game, all the while making notes as to what specifically made it such great fun. I feel like I learnt a lot from this, understanding what works and what doesn’t when it comes to design and mechanics.

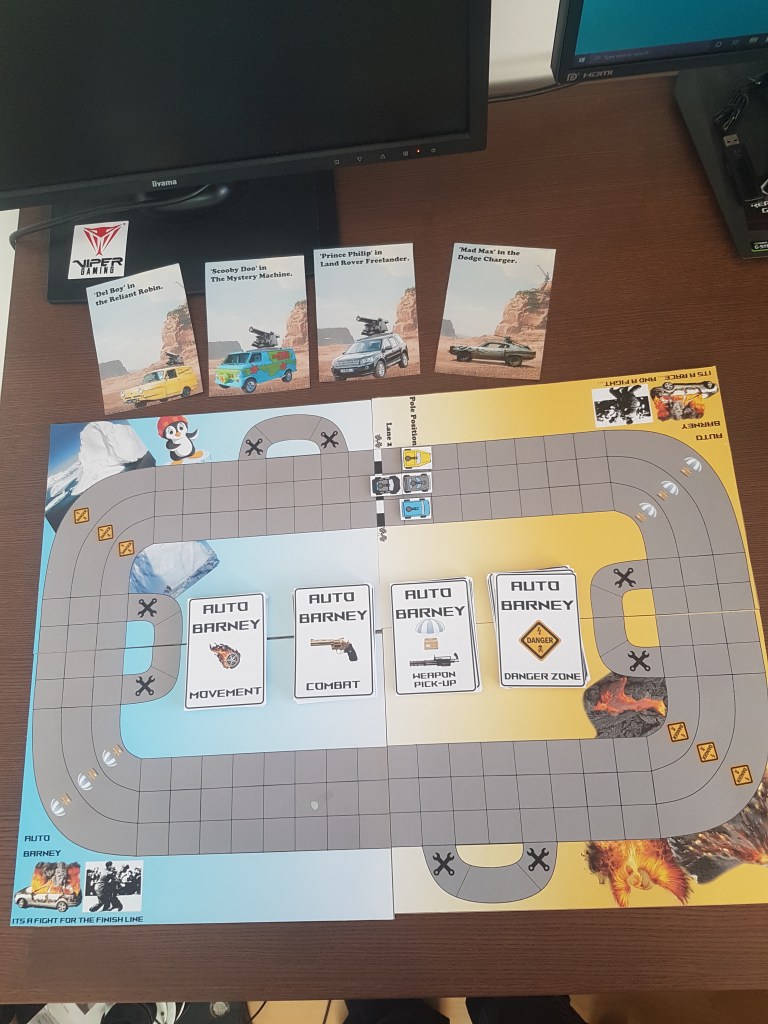

Assignment two allowed us to advance with our new-found knowledge about game design and produce something. In this case, a non-digital game. I made a board game from scratch for the first time in my life – ‘Auto Barney’, and had fun building it and testing it with my peers. There is a reflective piece elsewhere on this blog about the game, so I won’t expand any further on it here.

Overall, I would say this module was a crucial building block for anyone hoping to go into game development. It gave me a lot to think about. Understanding engagement loops, and the importance of solid design and mechanics is something I will carry forward into further study.

‘The skills you need’ module was aptly titled, and for someone who had been out of education for 25 years pretty useful. Research and referencing were the two main areas of focus and our assignments involved producing an academic poster and writing an academic report.

I chose ‘Microtransactions and financial ethics in computer games’ as my academic poster subject. I felt like it was a topic worthy of discussion as the phenomenon of ‘loot box addiction’ had been in the news and a former work colleague had developed a compulsion to buy player packs on the Fifa football game to the point where he spent £900 in two months. He realised he had developed a problem and deleted the game at that point! It was fascinating to discover that Electronic Arts who produce Fifa football were historically the first to introduce microtransactions to games!

For the academic report I chose AI and the Technological Singularity. Another fascinating subject, the emphasis on this assignment was good research techniques and clear and extensive referencing.

A worthwhile subject, I feel like I have learnt techniques and skills that will be of use in future study. I had only ever used Harvard referencing previously, so learning to use IEEE was essential as it is the standard for computing related topics.

Semester Two

The second three modules consisted of Contextual Studies, Game Design Fundamentals and a Game Design Project.

The game design project involved producing a working computer game as part of a team. We developed ‘The Tree and the Bashful City’. A separate detailed blog on this is to be found elsewhere on this site, so I won’t expand on it any further here.

Contextual Studies involved a brief overview of a number of topics and a weekly hour-long discussion group. Many of the topics we looked at were interesting, and the weekly discussions gave insight into the opinions of others. Everybody looks at the world through different eyes and it certainly proved that not all people think the same.

Our assignment for this was to produce a short reflective piece of writing on the 6 topics of our choice. I learnt a few interesting facts and any expansion of knowledge is to be welcomed.

Game Design Fundamentals proved to be my favourite module of the foundation year. We were to study two pieces of software that are complex yet almost essential to anyone wanting to progress in learning to make computer games:

Autodesk Maya – Industry standard 3D sculpting, rigging and animating tool. Used by thousands to create 3D objects and characters of professional standard. We were tasked with creating a 3D sculpted model inspired by the ‘fallout guys’ characters.

I had a feeling I was really going to struggle with this task, but I enjoyed the experience of starting with a square block and finally having a passable character sculpted from it. The software is deeply complex and versatile, but through this process we learnt some fundamental skills. I feel a lot more prepared for this kind of work going forward into future years as a result!

Unreal Engine / Editor – Again, industry standard software. A game engine well known and widely used to produce professional AAA titles. We were tasked with building a level for our Maya character to play in. Some simple mechanics, moving objects and obstacles were to be included. A win/lose condition was to be attached and some animation of our ‘bean guy’ character was to be included if possible.

I really enjoyed this task. I loved getting to grips with Unreal engine – was impressed with its versatile ‘blueprint’ alternative to coding facility and can’t wait to get a deeper understanding of how it works. The potential for producing quality games is immediately visible and I can see why it is so widely used in the industry.

Overall this module was an extremely impressive grounding in creating 3D animated characters and level creation. Some of my fellow students really excelled in this module and I look forward to seeing others work. My own results are less than perfect (I have posted a link to a youtube clip of my character and level at the end of this blog), but as a first attempt I am really pleased and look forward to progressing further.

In conclusion

Well what a year! From trepidation about what to expect, concerns over the effect of the Coronavirus epidemics impact and personal worries as to whether I was still capable of study at this level I feel like it has gone surprisingly well!

It has been an overwhelmingly positive experience. I suppose I expected a much gentler introduction with it being a foundation year. I had no idea I would be left with a sense that I have made a huge level of progress towards the ultimate goal of being able to develop computer games at a professional level.

Thanks to a bunch of enthusiastic, helpful and friendly fellow students and a couple of great lecturers it has flown by and I have learned more than I could have imagined. I feel more confident in my own abilities moving forward and look forward to starting the first year in the autumn.

My summer plans are to complete some courses in C++ and Unreal Engine Blueprinting and to take part in a small game making project with some fellow students hoping to add to our portfolios.

‘The Tree and the Bashful City’

A reflection on the development and presentation of the game

Starting from scratch

When we were handed the details for this assignment, I quickly realised it was likely to be the most challenging module in the whole of our foundation year. We were tasked with developing a game between the whole group (around 9 students at the start of the project) and ultimately to present and demonstrate the game in front of lecturers and masters level students, who would provide critical feedback on our efforts.

I think like everybody in the group I was both nervous and excited at the prospect of facing a new challenge. This was the first time any of us had teamed up to make a game and unlike a solo project there was also the added fear of letting down your peers and not being able to make a valuable contribution to the game.

We started with a randomly generated title for the game ‘A Tree and the Bashful City’. My initial reaction was that it was going to be a really tricky title to work with and had no instant thoughts as to the type of game we could make to fit the name.

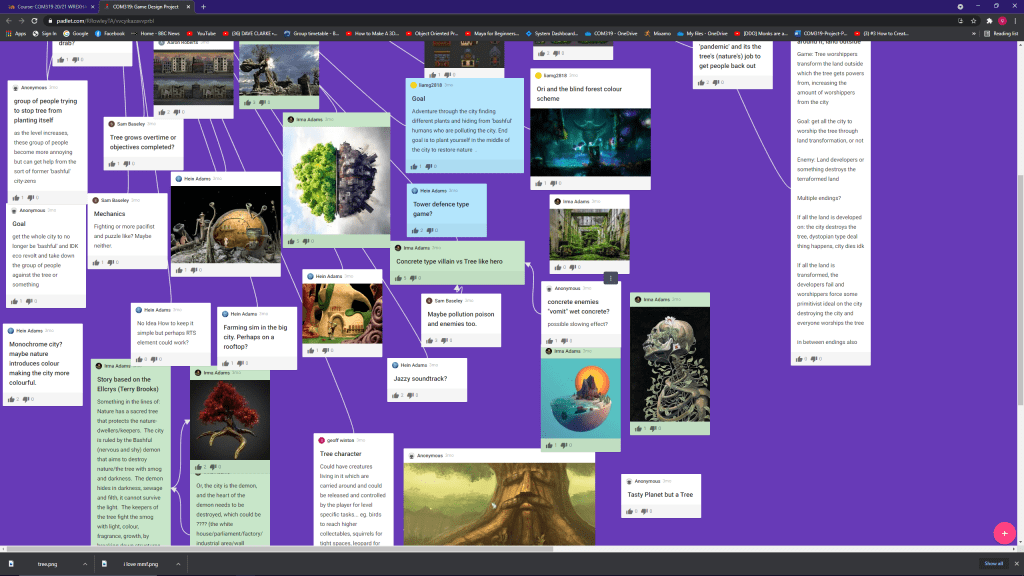

Luckily everyone in the group was instantly enthusiastic and imaginative, with a group padlet used to express initial ideas for themes and gameplay. Slowly we narrowed down something that might work as a playable game and fit the title.

Between us we quickly decided that a nature vs industrialisation theme would be both appropriate and unusual. We wanted to do something more interesting than just a basic platformer and considered various types of game. Considerations were given to genres including a ‘horde’ type game (similar to ‘We are billions’) and purer real time strategies like ‘Age of Empires’.

I was really impressed how quickly we were able to communicate well as a team. There was to be nobody appointed as a project manager and I am glad this was the case as it meant that all ideas were given consideration and nothing outrightly dismissed unless the entire group agreed.

So, the initial plan was to create a RTS style game with a nature vs industrial pollution theme. We were to use a basic game engine (Multimedia Fusion) to develop the game. The game would be 2D, possibly with an isometric viewpoint and the art style would be pixel-art with brighter colours for the nature side, and drabber colours for the city.

Once we had a basic foundation in place, I felt encouraged that we could work well as a team and actually end up with a playable game. Exciting times!

After a couple of team members drop out of the project, we were down to a hard-core of 7 people. Fortunately, we had a fairly even split as to who would like to work on which area of the game with one member enthusiastic about providing a background story, three talented artists, and three (myself included) who would prefer to work on the development side (coding and mechanics etc). This balance ultimately helped tremendously with the smooth creation of the game.

Initial feelings of trepidation when presented with nothing but a title to work with quickly disappeared as the mists cleared and a workable idea emerged. I feel like I learnt a lot from this process, and the brainstorming padlet sessions and discussions were a valuable experience to carry forward to future team-based projects.

Multimedia Fusion development

Learning to work with a new game engine is a challenge in itself. Multimedia Fusion, despite its relative simplicity is no different. It does not involve coding in its purest sense, but a tick-box system to generate game objects and attach condition checks and events to them.

My only experience with game making had been a brief project making a simple platformer level with a very different engine (Gamemaker Studio). The only similarity being that you are working with 2D sprites.

On first glance, I expected Fusion to be relatively easy to learn how to use but it is surprisingly versatile and complex on closer inspection. Jack provided some excellent tutorials on the software and coupled with youtube videos and dedicated forums we were able to glean enough knowledge to make a start on gameplay.

As the development side of the team, one challenge which we anticipated and had to deal with was working separately on various areas and amalgamate our work into one final master copy. Github was not an option, and I was worried this process would not go smoothly. Close communication was key, and I think clearly defining our tasks on each sprint in Jira was essential to prevent us overlapping on certain areas of development. Between us we managed to iron out any problems as we bound our tasks together.

Each week we improved on the version of the game, after initially using placeholder objects we were able to gradually implement the work of the art team and our efforts started to look and feel like a playable game.

I was impressed how quickly we made progress and I feel that our weekly meetings and use of SCRUM methodology was vitally important in this regard. Tasks were clearly defined each week and meetings ensured we were all happy with the direction the game was going in.

Ultimately Multimedia Fusion proved to be occasionally difficult to develop a game with. It can be temperamental and leave you with the confusion of why something works one minute and then seems not to despite not having made any changes! I think the three of us who were heavily involved in using the software all went through these moments of sheer frustration.

Another issue we encountered in using Fusion was optimisation issues. For example, when too many enemy units were active on screen, the game would slow to a crawl and become unplayable. This was due to the engine struggling with so many loops and events taking place every tick of the game. This curbed our plan to make the game similar to ‘We are billions’. The engine simply would not cope with huge hordes of enemy units and their health bars on screen so eventually we went with a tower defence type game, with limited numbers of enemies appearing in small waves at intervals.

As a team we were fairly flexible as to the end product, so the game adapted as we progressed through development. I enjoyed this flexible approach and despite the occasional moments of frustration, I enjoyed using Fusion overall. As a team we all collaborated well to deal with any problems or issues with getting the game running. If one of us couldn’t find the solution, we looked to the others for help, and it was always forthcoming. A great team working experience.

Demonstration day

The date for our presentation of the game felt like it came around far too quickly! However, we were all happy that we had something that looked nice and kind of worked as a game.

There were a few outstanding bugs, some issues with animations and unit movements that we had to iron out at the last minute. The story frame was added and we now had a main menu screen and win / lose screens in place too.

As a group we decided we would give a quick powerpoint slide show and say a few words about our overall contribution to the game. We had hoped to rehearse this beforehand, but for one reason and another it didn’t happen. In retrospect I think it would have been a much better presentation had we done this, as everyone was a little nervous and I was not alone in stumbling over my words slightly while speaking over the slide.

The demo of the game went ok, I think most of the elements in the game were on show and functionality was demonstrated. We had mostly positive feedback afterwards and I think people were impressed by the artwork and the fact that the three artists style remained consistent so you couldn’t really tell it had been done by different people.

Gameplay needed a little polish and in retrospect I wish we had more time assigned for testing and balancing the game. Testing the game on more players outside of the group throughout the whole process would also have provided valuable insight.

Final thoughts

In conclusion this assignment was a really enjoyable experience. Extremely useful preparation for next year on our journey into learning game development.

Becoming familiar with close communication, team working and SCRUM methodology / Jira will prove invaluable as we move forward onto more ambitious projects, and eventually the professional environment.

It was a pleasure to work with such enthusiastic team mates and I feel more confident in my own abilities as a result.

Would I make any changes to our approach next time? Possibly only concentrating more on getting the game functioning perfectly early on in the process. I think we got a little bit excited about implementing the artists work early on to make it look good and then ironed out issues with how the game functioned a little later on. Using placeholder art until the game runs fine is probably the best way forward, but it was the first time any of us had been through this process so a lesson learned!

Auto Barney – A reflection on the first playtest!

COM326 Assignment 2 – Create a non-digital game

When I took a first look at the assignment brief, I was both excited and nervous at the prospect of having to make a game from scratch and test it with my fellow students. I am sure everyone was experiencing the same mix of feelings. We were going to get to make our first game! Very exciting! No narrow brief on what the game should be about or even the type of game, the only caveat being that it was to be a non-digital one. This was to be then played with our peers and reflected on. This was the nerve-wracking element. Complicated further by the fact that we are bang in the middle of a global pandemic and national lockdown. We are yet to set foot in the University buildings despite getting to the end of semester one. Games were going to have to be played via the internet and webcams. This added a much greater challenge to the task ahead!

Coming up with a workable idea and how to make it function via webcam was going to be tricky. I briefly considered using tabletop simulator but felt this would be a bit of a cop-out, as the task was to make a non-digital game.

I quickly settled on wanting to make a board game above all other choices. I love board games just as much as I love computer games. I grew up in a family who all loved them too, so it would be a regular rainy Sunday afternoon pastime and chance for us to get together.

So what type of boardgame was I going to make? I remembered an old horse racing board game I loved as a child – ‘Totopoly’. It was great to see peoples competitive spirit come out, and there was genuine excitement when you were neck and neck with another player racing round. I had recently watched the Mad Max: Fury Road film again as my girlfriend hadn’t seen it and was a fan of the original. I thought it might be interesting to try and create some kind of Mad-Max style ‘racing with combat elements’ type of game, with a bit of Mario Kart influence thrown in.

So using Paint.Net and Aseprite I set about designing and making a board, counters and cards. I quickly abandoned the idea of using rulers etc to measure distance round a track in favour of a grid system. I felt it was important to keep it relatively simple as we were not going to be able to all sit round a table and test it. I would be moving the others counters as well as drawing their cards for them for any movement and combat.

I decided not to test the game at all before our designated testing day. Part of me wanted to out of curiosity, but part of me was equally fearful that it simply wouldn’t work for some reason, or that it might not feel fun to play. I had already spent many hours working on it, and it was far too late to start again from scratch. I had some arbitrary figures for things like hit points, range and damage in my head, but I had no idea if these would pan out to be playable.

Testing day arrived and I set up the webcam over the board and checked that the image was clear enough. This involved a bit of a ‘blue-peter’ style set up with half a garden cane and some duct-tape, but it seemed to work well enough. It was interesting to see what other people had come up with and all the other games were fun to play. I think we were all a bit nervous having never actually met each other but everyone seemed enthusiastic about the playtesting session.

We each had a 45 minute window to test our games and emerge with enough material to reflect on our games. I went second to last out of the five of us. I was quite conscious of the limited time frame but hoped we could squeeze in one full lap in the 45 minutes to give a fair reflection of the game and some kind of closure to the test. With four players I offered to toss a coin to determine who would start in pole position, and who in lane 2. Typically enough I managed to get heads for all four players so a re-toss was needed. We ended up with two in pole position lane and two in lane 2 – a fair result.

I had tried to make the game as light-hearted and fun despite its competitive nature. Players were assigned their own characters including Scooby-doo, Del Boy and Prince Philip as well as Mad-Max. These were purely cosmetic. No advantages were added by ending up with any character although that could be an element for consideration in retrospect. Perhaps one with a slower, stronger vehicle and one with a faster, more fragile one. I wanted to keep it simple.

I briefly explained most of the rules but I wanted to get things moving due to the limited time frame so there was definitely an element of learn to play as you go happening. I didn’t want to spend 10 minutes going through every intricacy and thought it would be better to explain the basics then get going. The players seemed enthusiastic from the start and despite the fact I was having to draw all the cards for movement etc and show them to the camera, the race seemed to move at a reasonable pace. I think had we all been sat at a table playing it could run even more quickly with practice.

The one area where I wanted to keep an element of secrecy as to what cards had been drawn by a player were the weapon pick-ups. I felt it would be a bit more fun if other players didn’t know what secret weapon their opponents had up their sleeve to use on them at any moment. For this reason I asked the other players to turn away from the screen when someone picked up a weapon.

Having not done a great job at explaining the combat mechanics of the game at the start, nobody was really attempting a shot or ramming early in the game. In retrospect I would have spent a bit more time explaining the pros and cons of attacking other players and we might have seen more action along those lines in the earlier stages! As it was people just seemed happy to race along to start with.

I had set the danger zone cards so that there was a 1 in 3 chance of damage so high you went into limp mode. Everyone has to draw a danger zone card on passing through and I must have done a very bad job of shuffling the cards as sure enough the first three through all ended up in limp mode!

I had decided that limp mode would entail a movement penalty (I settled on restricting the max to 2 spaces per turn). I also decided that being in limp mode would mean that you couldn’t attack others and were forced to enter the next repair area on the track. The repair area was there to slow a player down as you could only move through at 1 square per turn, emerging with full hit points again. I was concerned that one player might end up very far in the lead while others went through the whole limp mode scenario, but there was always the chance that they might come a cropper at the next danger zone so I hoped this would balance things out somewhat.

In the playtest I think everyone went into limp mode at some point. The suggestion came up that players could choose to limp along rather than being forced to pull into the repair area. I thought I would let this idea run to see what happened – would having a maximum 2 for movement allow those who had gone through the repair area to catch up? It was the first playtest so felt it was probably important to not be too rigid with the rules and be a bit more explorative to see what did and didn’t work.

In practice one player did get several spaces ahead and proved to be ultimately uncatchable, although this was down to some bad luck when attempting to fire on him by others. A good win for Liam playing as ‘Prince Philip in the Landrover Freelander’.

So was it fun to play? Well the players seemed to react well and were certainly enthusiastic and competitive, and I hope we had a bit of a laugh playing. Feedback and suggestions were inventive and constructive and all worthy of consideration. I think the players felt that losing all your hit points and being in limp mode needed to be a harsher penalty. That being hit by a weapon successfully while in limp mode could result in no movement the next turn (missing a go effectively) might work better. I am inclined to agree.

Other suggestions that I think are worthy and would certainly make it a better game would be the use of short-cuts that pass through a danger zone, or use of the ‘racing line’ at some risk. Where obtaining an advantage in the race vs the risk of damaging the vehicle becomes a choice the player has to weigh up.

Overall, for a first test run I think it went ok. It was played with more enthusiasm than I could ever have hoped for thanks to a good crew of enthusiastic play testers. We managed to complete 1 lap in the time allowed and it was a relatively close run as players approached the finish line.

First attempt at 3d modelling with Maya

Thanks to Shane at Game Dev Academy for the YouTube tutorial!

Here’s my (less than perfect) results

Fantastic tutorial available here :

The curious world of the hobbit

A look at the Helen Stuckey case study of the game.

Helen Stuckey has done a great job of examining this game. Her piece is a well written case study that observes many aspects that make the game so special and ambitious for a game released in 1982.

She clearly sets out her intentions early, focuses on what makes the game unique and how well the developers did in fitting a relatively complex game into a 48k machine.

‘This paper explores The Hobbit’s dynamic gameworld. Reflecting

on the game’s design and its relation to Tolkien’s novel, the

discussion draws on the voices of players and their diverse

experiences to help explain how its database driven systems and

randomised routines made its simple world alive with possibility.

I also consider the importance of the analogue tasks of map

mapping and note making for the micro-adventurer..’

The writing is formal in style and certainly not that of a review. It takes a historical look at the games development with a clear account of the rise of the publishers Melbourne House. From the article we can see how popular computer games had already become in britain by this time, with the industry valued at $30-35 million.

The writer admits they had no personal memories to draw on from playing the game but did conduct interviews with both the developers and former players of the game. The piece is more of an examination than a critical appraisal, looking at the mechanics of the game and players reactions to it. It does make some observations on how impressive the game was for the time, not many text adventures had accompanying graphics to help set the scene. The games dynamic world with non-player characters performing actions out of sight of the player is also praised as being unique at the time of release.

Stuckey also observes the importance of the book itself in relation to the game. It is interesting that some of the puzzles will require the player to have read the book in order to solve them (the book was bundled with the game for some releases).

She looks at the ‘lost art’ of game-side map making. The only way to complete a game of this nature is to have a pen and paper beside you to map your progress, otherwise risking getting completely lost.

She also notes the imperfections in the game. There are bugs, and she remarks on the difficulty in ‘de-bugging’ complex games of this era. Particularly when, like the Hobbit, they are written in assembly language in order to squeeze as much as possible into limited available memory! This was a common problem in game development at the time. As Sid Meier (Civilisation) states in his autobiography – it was half the battle in making a game back then. Something had to give with such limited memory available, and it is testament to the developers that they managed to include some rudimentary graphics alongside a complex text adventure and pioneering AI!

I was 9 years old when this game was released and already a big fan of the book so I am gutted I never got to play the game. I never owned a Spectrum 48k. Starting with an Atari VCS, I eventually jumped to a Commodore 64 but never remember coming across the game or seeing any of my Spectrum owning friends playing it. This case study was a great examination of what should be considered an important piece of game development history.

Subnautica: a case study

Why Subnautica?

Subnautica has captivated me more than any game I have played this year. It has some areas of design development that are worthy of deeper examination. It has been referred to by some as an underrated masterpiece and I must agree. This case study will attempt to get to the root of why it’s such a brilliant game, while considering design decisions based on gameplay, mechanics and any limitations faced by the developers.

Subnautica is essentially a survival / exploration / crafting game. Unusual in that it is set almost entirely underwater on an alien planet, the relatively small development team (Unknown Worlds) have managed to create an extremely well balanced, absorbing game. Open world with a great storyline that helps prevent any boredom from pure exploration without dragging the player down a linear, hand-held path. The game opens with the player being jettisoned from a spaceship (‘the Aurora’) in a life-pod which lands in open water on an alien world. From here, the player begins an adventure which can be lonely, breath-taking, disorientating, exciting, truly terrifying and ultimately deeply rewarding.

Development and early access

Unknown worlds faced many challenges during development. Despite a relatively successful previous game (first person shooter Natural Selection 2), funds were tight. After 18 months of work bringing Subnautica from prototype to minimum viable product, funds had run out. It had a successful demo at the PAX East game conference 6 months earlier, so the decision was taken to bring the game out in ‘early access’ in December 2014. The game would spend just over 3 years in continual development with early access, the final release taking place in January 2018.

Early access can be a gamble. On the one hand it allows feedback from players as to progression and buys some time to create the finished product. On the other hand, players can be turned off by the lack of polish and sheer number of bugs that are prevalent in unfinished games. Thankfully most players loved the game even in its early stages and saw the promise of something unique and exciting in the making.

The developers included a clever feature in adding ‘one button feedback’. Hitting the F8 key at any time during gameplay would bring up a feedback sheet where players could report bugs or give positive or negative feedback. It would record the players location in the gameworld at that time, so the developers could quickly fix or change anything needed. The data collected was available to everyone, not just the developers. In this way the players themselves shaped the game and contributed hugely to the finished product.

Design decisions

Despite early access games being largely player driven, occasionally developers need to dig their heels in and stick to their original plan. Many Subnautica players were asking for guns to be included to fight against the more aggressive creatures in the game. Despite their previous game being a gun-heavy FPS, lead developer Charlie Cleveland decided early on that he was frustrated with the constant gun violence in his home country (USA) and wanted to create a game that allowed people to escape from this. This decision was directly influenced by development starting shortly after the Sandy Hook school massacre where 20 children aged 6-7 were killed.

Combat was removed from the game loop in favour of the player collecting materials for crafting items to progress further and deeper. Oxygen tanks, an underwater base, two different sized submarines, a mech-suit with drilling arms and many other items can be crafted. So, having removed combat, how did they go about keeping excitement levels high in what is essentially an underwater exploration game? They introduced huge predatory ‘leviathan class’ creatures.

These creatures, particularly the ‘reaper leviathan’ (above), are terror inducing. The underwater gameworld is divided into 12 distinct ‘biomes’ each with differing plants and creatures. Each biome flows smoothly into the next as the underwater landscape changes. Some of these biomes contain creatures which can attack the player, damage submarines to the point of destruction and leave the player swimming away for their life! Many videos can be found on Youtube of twitch streamers ‘jump-scares’ as they encounter these creatures. The developers have joked that they created a horror game ‘accidentally’.

The gameworld is quite large, around 2km square and around 1600m deep in some areas. The player never actually has any kind of in-game map (a compass can be crafted to help with navigation). You know you have reached the edge of the play area as the landscape drops away sharply to unreachable depths. This is quite a clever technique to keep you in the gameworld as it doesn’t take away from the sense of immersion. There are no invisible barriers, just no reason to travel any further from the play area. Graphically the game is impressive. The world was hand crafted after the developers abandoned using a procedural generation technique as being too unrealistic. Placing every plant and resource obviously lengthened development time but it was well worth it. A popularly requested feature was multi-player, but this was never implemented as the developers felt they would have to start the game from scratch.

Early access and feedback provided the developers with great insight into how players reacted to the overall gameplay. Emotional design was a concept held as important. Provoking emotional responses in players like the stress of running low on oxygen, a sense of ‘the unknown’ as you enter a never explored biome or just floating above an abyss wondering what you are to discover down there can be awe inspiring.

Game loop and mechanics

Players start the game with very few possessions. The most important is a hand-held ‘scanner’. This can be used to scan creatures, plants and any parts of wreckage from the crashed spaceship that can be found scattered around the seabed. Scanning wreckage unlocks ‘blueprints’ of useful items that can then be crafted from gathered materials. Data from the scanner is uploaded to a ‘PDA’. This can be viewed at any time and shows all sorts of information including your inventory.

Placing constrictions on players is an important game mechanic employed by Subnautica. Without them the whole gameworld would be open to immediate exploration and take away the sense of progression and achievement that is so important to keep players interested. The most important of these is oxygen.

Players have only the oxygen they can hold in their lungs on starting and this quickly ticks away restricting how deep you can dive down before returning to the surface or risk drowning. As more materials and blueprints are gathered, deeper longer exploration is unlocked. This is a compelling mechanic and keeps the player coming back with a desire to go deeper and explore further. The mystery of the depths keeps players returning to the game, what beautiful sights or terrifying creatures are to be found? The sense of power and freedom when you craft your first underwater vehicle is immense. The players sense of vulnerability gradually reduces on progression but never totally disappears.

The survival mechanics of the game mean that a player needs to keep a watch on their food and water levels. These meters gradually tick away until replenished and can result in death through dehydration or starvation if not addressed. Water and food are easy enough to come by and the mechanic is not regularly intrusive enough to frustrate players, but will encourage them to be organised and prepared if embarking on a long journey to the depths for example.

Final thoughts

The danger with exploration games is player boredom. Subnautica never feels tiresome. Radio messages from other abandoned lifepods attract the player to new biomes and gradually a story develops. Infected with a virus on landing, the player must ultimately find a cure for this and build an escape rocket. Finishing the game leaves you satisfied with a feeling of a beautiful, exciting adventure completed.

*** WARNING – THERE MAY BE A LITTLE BIT OF SWEARING IN THIS YOUTUBE VID 🙂 ***